Minas

They say there is gold under my land

Jorge Cordero is not an isolated case. In fact, already 15 million people in Mexico have been displaced from their land due to mining, the industry of extracting valuable minerals from the ground. Mexico is a country with abundant natural resources such as gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, natural gas and petroleum. According to the Ley Minera, the valid mining code from 1992, regulating all mining activities, mining has priority over any other land use, including agriculture and housing. The conflict between the economic benefits of the industry and the negative impact it has on local communities is everlasting. Generally, the financially rewarding outcome of mining receives more attention than the people affected by the industry. Who are the ones to pay the price.

Mining in Mexico

Mining has always been a major factor in the economic and political history of Mexico. Let alone the colonial-era from 1521 to 1810 and the Spanish quest for precious materials. Starting 1810, the struggle for Independence in Mexico obstructed most mining operations for a period of sixty years until the mining sector was reopened for foreign direct investments under the liberal regime of Porfirio Diaz in the 1870s. British and American companies seized their opportunity, broadly equipped with new techniques and tools, eliminating Mexican competitors. With the mining sector becoming an American reserve and source for some leading fortunes of early twentieth centuries capitalism (such as Guggenheim), grounds were laid for the Mexican Revolution from 1911 to 1920. The nationalization of the oil industry (establishing the monopoly of PEMEX) reasserted national control over Mexico’s natural resources. Prohibiting foreign mining firms from owning over 50% of mining projects.

These policies were soon to be revised, when Mexico’s economy was weakened by the 1982 debt crisis and the 1986 drop in oil revenues. Now the political focus laid on reopening the Mexican economy to foreign direct investment and external technological modernization. In particular the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 marked the renewed liberalization of the Mexican economy. These measurements facilitate land privatization and the entry of foreign corporations. In combination with the new Ley Minera agreement, the NAFTA and rising prices of precious materials encouraged foreign mining corporations to return to Mexico. The systematic commercial exploitation of silver and gold deposits had its revival. This time, however, Canada became one of the principal players.

Canada’s takeover

Since the 1990s Canadian mining is almost omnipresent in Latin America, with the expansion of gold projects across the whole continent. Within four years, the number of properties owned by Canadian companies almost quintupled (52 to 244). By 2005 Canadian companies controlled close to two-thirds of the Mexican Mining Industry. Showing that the market liberalization for foreign investments swept away the effort of keeping natural resources as a national asset and foreign investments at a minimum. Figures from 2010 show that nearly 80% of 718 mining projects currently under development in Mexico are under Canadian control. The main mining states are Zacatecas, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuilo, and Durango, where significant gold, silver, copper, iron and zinc deposits can be found.

Economic benefit vs. human rights

Mexico’s mining sector reached an investment high of US$7.6 billion in 2012, while international prices for most metals keep rising. For some the economic yield seems to be argument enough for a persistent expansion of the mining industry. Companies take financial risks in account, calculating high-risk investments, while closing their eyes to the social and environmental impact caused by mining. Arguments like increased job opportunities and development of rural communities try to legitimize the development and expansions of many critical projects, discounting any negative affects, which often only local communities are aware of.

Currently in Mexico, there are no public audiences required by law, prior to mining. This leaves local communities often as the last to find out about mining projects in their environment. A lack of communication between the corporations and the people affected leads to critical situations. False consultation or deals made between corporations and so-called community leaders happen without any community involvement.

The case of Sierra la Laguna

As one case of many, the personal story of the Cordero Family in the Mountains of the Sierra Laguna in Baja California Sur, illustrates the mistreatment of local communities, a family left with few instruments to advocate their rights.

The family of Rancheros, the Corderos, live in the Valle Perdido in the Sierra Laguna. A protected biosphere and simultaneously planned construction site of the Paredones Amarillos gold mine (now called „Concordia“). The Corderos have been living on this land for more than three generations. Paying taxes makes them legal proprietors of the Rancho las Palersitas. As rightful owners of this particular land, they find themselves challenged by a multi-million-dollar company called Vista Gold Corp. A Canadian Company, seeking to acquire their land. For Vista Gold, the Sierra Laguna holds a truly lucrative deposit of natural resources – literally speaking a gold mine – with an ounce (~30g) being worth US$1000. For the people living in Baja California Sur, the Sierra holds the only fresh water source in the region, preserving an inimitable biodiversity of flora and fauna. For a reason the UNESCO declared the Sierra la Laguna a World Biosphere in 1994. The contamination of such water reserve would mean jeopardizing the marine life of the Cortez Sea and coastal ocean, as contaminated ground waters flow into the ocean. An area of sovereign nature, accommodating calving whales, dolphins and coral reefs makes the area a sought-after place of rehabilitation.

The region of Baja California Sur often faces water scarcity, especially in the hot seasons. With clean water being such precious commodity, the contamination of a water source such as the one in the mountains of the Sierra la Laguna seems unforgivable.

Getting gold

The process to extract gold from the mountains in the Sierra Laguna poses a risk of destroying the diverse sea life and rich biodiversity of the mountains, as well as severe drinking water contamination. An open-pit mine, the construction which would be needed for the mining process in the mine of Paredones Amarillos, works with the chemical Cyanide, which dissolves the gold into liquid, facilitating its collection. The high quantities of rock that have to be treated only provide mere grams of gold, leave vast amounts of toxic waste in the soil. The project plans of the Vista Gold Corporation intend to store the cyanide infested rock lavage in a dam, for unlimited time. Several occasions proof high possibility of these storage dams to break, causing a devastating scale of destruction. Just recently, in November 2015, the world witnessed the dam burst at an iron ore mine in Brazil, killing 12 people and polluting the entire river Rio Dolce with toxic mining waste. The 60 million cubic meters of mine waste cut off drinking water for a quarter of a million people. The waste spill has now reached the Atlantic Ocean.

Another hazard of open-pit mines is the one of “acid mine drainage”. When sulphur-containing rocks are exposed to air and water it creates sulphuric acid, which can cause heavy toxic metals to dissolve and drain into the watershed. The risk of a mine drainage appeared to be likely in the case of the planned gold mine of Paredones Amarillos, prompting hundreds of people to demonstrate against the construction of the mine, with Vista Gold Corp. facing high local opposition.

The story of the Corderos

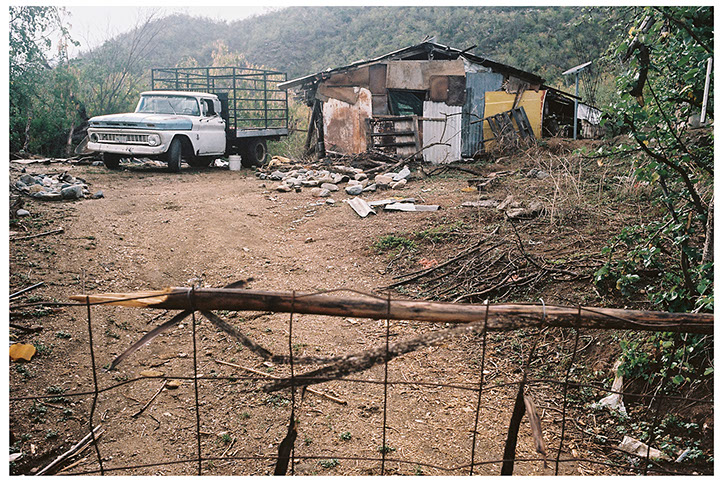

Yet the strongest protest emanated from the last individual land owners in the area of the Sierra Laguna, the Cordero family. Refusing to sell their land to a big mining company like the Vista Gold Corporation, they wage a bitter struggle against an industry that will stop at nothing to succeed. According to the Cordero family, executives of the mining venture who started building work without holding any legal permits, unrightfully accessed their land. In the process of developing the open-pit mine, the houses of the Corderos were destroyed. Without any official support the family chased the mining workers off their land, deciding to protect what was left. At the moment the family lives in campers, a replacement of their destroyed house. The illicit actions of the mining authorities make it impossible for the Cordero family to leave their land. They have no choice than guarding it themselves, constantly fearing to be forced off their very own property. The Corderos have filed a court order, on which decisions are still pending. Nevertheless, the conflict seems to exceed legal frame. So far the Corderos have even received death threats by security guards who were hired by the mining venture and wanted to access the land, which concludes that illegal pressure is being applied to force the family off their land.

Numerous activists supporting the struggle of the Cordero family, especially the organization “agua vale mas que oro”, anticipate corruptive behavior among the deciding organs for the authorization of permits for the gold mine. The registration office, which creates the permits for mine activity, was supposedly pressured by the Secretary-General to sign permits on his authority. Regardless of the truth of such allegations, organizations call for action and awareness of the impact of mining projects, in regards of our environment and people’s rights to property and basic commodities.

Water

Profit orientated companies and ventures often downplay the risk mining activities pose to the environment. In the case of the Sierra Laguna, the proposed gold mine does not only threaten to contaminate the pristine area of the Sierra Laguna Biosphere, but foremost could destroy the entire watershed. The aquifers below the mountainous region provide drinking and irrigation water to most of the people of the arid state of Baja California Sur. Therefore thousands of people and countless wildlife in the reserve desert rely on this water for survival.

Baja California Sur is Mexico’s driest state, making water an even more precious commodity than in other parts of the country. Baja California Sur has an average of 160mm of rain per year, compared to 760mm of rain per year for the country as a whole. Numerous towns of BCS are running out of water, while the state’s population growth is the second fastest in the country. Preventive steps need to be taken soon, to avoid enormous environmental, economic and public health consequences.

Text Sophie Strobele

Full Photo Story: http://www.theodegueltzl.com/rancheros.html